Mehta, telling his story as a nostalgic ex-pat of India, approximates the art of being "in-between," of finding home in mobility, and finding truth in storytelling.

"There are many Bombays; through the writing of this book, I wanted to find mine."

- Suketu Mehta

Note: Throughout the piece, Mumbai and Bombay will be used interchangeably as a name for this city. Bombay was the original name, derived from the impressions of the Portuguese discovery of the paradisal island. They called it Bom bahia, Buon bahia, and Bombaim, all meaning “good bay.” Indians moved to change the name to Mumbai not as a method of decolonizing or de-anglicizing the name, but as a process of de-Islamicization, to erect the false notion of a decidedly Hindu state. Renaming became a trend for the Hindustani idealists.

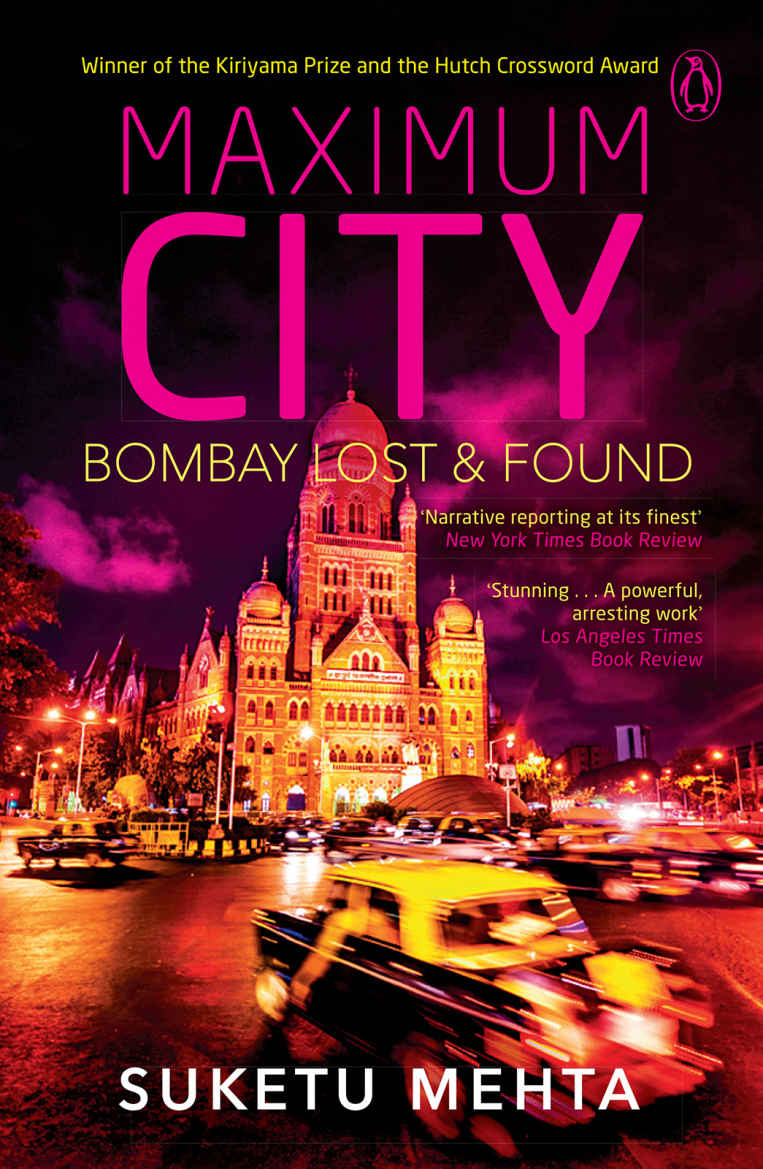

Maximum City was written to unearth the secrets behind Mumbai, India’s principal, coastal metropolis. It does more than unearth. This wonderful book probes Mumbai with deft, poetic grace, exposing that cities are never cultural monoliths. I saw this first hand over the Winter, and this review will read much more like a journal entry because of this. It will be personal as well as exclusively critical. There is always a wealth of wisdom waiting to be unearthed in the knowledge of one’s cultural history, and I can’t not share all that I learned while reading this book on the plane into and out of Mumbai — where my parents grew up, lived and worked.

The book is written entirely off of Mehta’s journalistic inquisitiveness — it’s laden with exclusively illustrious interviews with menacing sahebs (regional Hindu/Muslim mob bosses), victims of religious violence, and jaundiced Bollywood celebs in their true, unidealized form. The term “saheb” actually used to refer to European subjects in Indian colonies, a representative word for British regality and Indians’ colonial servitude to their leaders. India is still dealing with its colonial past and the pitfalls of decolonization. In Maximum City, we learn a lot about how Brown skin relates to white in modern Mumbai, and how colonialism had added to the multiple heads of this city, embroiled in religious massacres with triple-digit casualties and an evil underworld that seems to rule over.

“Every great city is schizophrenic.”

- Victor Hugo

This quote is peppered throughout the book and evoked in cases of extreme juxtaposition or absurdity. “Bombay has multiple personality disorder,” Mehta says, during our exposition into the city’s disjointed personality. With this, though, Mumbai maintains a powerful pulse. India does as a whole, with its anarchic traffic that operates on the mutual understanding that “I will not follow the lane lines or use my signals, so horn dedo (use your horn) if I get too close or you need to cross.” Even Satyajit Ray, the famous Bengali filmmaker, said that American city-dwellers operate in a mechanized, slavish manner to their masters/timetables while people in his home city, Kolkata, have “more contact with living.”

Dually, there is peace and anger equally distributed among this chaotic center of commerce — Mehta details many incidents where simple processes in India don’t work, like a line for a vendor, or having to fight for something as simple as parking in his own flat, or something as serious as getting proper gaslighting for the apartment. When he moved back to India, spoilt by American institutions that are responsive and modern technology that does not fail regularly, he woke up every day angry, every small irritation and every act of deception by crooked workmen accumulating into a murderous rage. Such is life in the city of commerce, where Mehta observes that no one values diligence — anyone can work hard. If you can properly cheat someone by being a bad plumber so they have to keep paying you to come back, you've done something novel and productive.

Even in such an angry country, peace is valued above all else, where sitting down to have your morning chai and meditating into the responsibilities of the day is always encouraged. The city values spiritual stillness, while simultaneously populous and squalorful. Hindu and Muslim gangs murder each other while Prime Minister Modi essentially sponsors violence towards non-Hindus (sound familiar?), while monks of all religions seek oneness and people of all ethnoreligious groups find communality in a Catholic church, where all caste and creed may congregate during Novena or any non-holiday, no questions asked.

Hinduism as a faith, as a civilization, does not ask that its followers abide by any dogma or belief in god. It even says in a Hindu hymn, the Shiva Mahimna Stotram, that "the different paths which men take through different tendencies, various as though they appear, crooked or straight, all lead to thee." India demands no official language, religion, or identity from its people, but is simultaneously the country of the "No," in Mehta's observations — a country that cheats its non-natives in any way they can take advantage of lacking experience. "That 'no' is your test," he writes. "It is India's Great Wall; it keeps out foreign invaders. India is not a tourist-friendly country." How can India be so identity-less and liberal — how can you see a Hindu carrying Muslim texts and keeping a rosary in his pocket, then see that same Hindu get beaten by a Muslim gangbanger for not falling under the same label as him? The answer is Power.

Power comes from having a gang, from taking advantage of existing religious contention to seize hearts and minds. In the past, and even somewhat now, the only way to make things happen was to pick a side: the Hindu Shiv Sena or the Muslim Dawood Ibrahim. Both gangs have been responsible for mass terrorism against each other. The conflict is never-ending, and these two opposing factions have legitimate political authority. Every slum building/demolition and every power deal must go through the local Saheb. Wealthy politicians touch his feet. "Shiv Sena" still dots headlines in the Times of India. Maximum City shows us that India is more or less run by gangs.

“Underworld is the wrong word to use for organized crime in Bombay, since it implies something hidden, something beneath. In Bombay, the underworld is an overworld; it is somehow suspended above this world and can come down and strike any time it chooses.”

- Suketu Mehta

Other than the fact that India is a sprawl of contradictions, Mehta imbues India with a brilliant grace, identifying it as what drove his nostalgic return to "home." He found, however, that his true self and home lie in mobility. It's the law of inertia, that once you unfix yourself and start moving, you can't stop. I learned from this book that it's completely okay to be in transit, to not feel "Indian" or "American." You don't have to choose. You can lean into whichever identity serves you best, whenever you want. "We are all individually multiple," reads the epigraph page of this book.

I didn’t grow up feeling like an Indian-American. I wasn’t nerdy, I couldn’t really relate to fervent academia, and I found it difficult to constrain my spastic creativity and burst-fire approaches to work into a rigid, Asian-American academic routine. I eventually learned how to handle myself, after some long adolescent years and marijuana abuse. The place I’m at now is the same place Mehta was — in a state of “in-betweenness.” I don’t feel, and I never really felt “Indian,” because my parents led their lives in America with very sparse pepperings of Hindu culture.

I heard Hindi songs growing up, I went to Temple every now and then, but I was assimilated since I stood among a menacingly white student body in Catholic school and pledged to an American flag. To a child, the ways in which my Indian-ness was denied seemed innocent, like it was supposed to happen but when someone dipped their thumb in red paint to impress a circular red dot in between my eyes, I quickly realized that the way in which I’d been othered was a distinct demonstration of the residual effects of overtly racist America in the 1900s, settler colonialism, and and “assimilate or get out” mindset. Most immigrants have to face this feeling, and almost every human has been in transition identity-wise.

This book was connective. It helped me find home in mobility, in my “in-betweenness,” and a deep, responsible respect for my Indian side where I acknowledge the backwardness of its foundational doctrines. Of course, actually being in India shaped my experience of this book. I “unfixed” my Americanness by acknowledging that there’s nothing wrong with participating in tradition. So long as the imperial American mindset lives, westernized people will see Indian culture in the light of pity. So long as the distracting influence of white feminism lives, they’ll see an Indian woman’s conscious decision to express love through servitude as a testament to her slavery. Commitment to one’s faith and household doesn’t have to be regressive. That’s not to say that Indian traditions are beyond reform or infallible — it’s a call to acknowledge the benevolent reminder of cultural relativism, and to disavow American exceptionalism.

I love the collectivistic, parochial values of Indian life as much as I love the liberal West and our generation’s earnestness in loosening the grips of social forces. In Mehta's storytelling, he found this connection as well. As the book unfolds, we watch as he learns to dance between being Indian and American, between pride and prejudice towards India. And through my reiteration of this story, I've learned the same.

Brigade Book Society Rating: 10/10

0 comments